Sifting through 100 ideas while breaking through the barrier of accepted wisdom

Market share is extremely important to a company, and I was impressed that Olympus was taking decisive action in response to a 2 percent decline in its share. I was extremely busy. We had completed the SLR camera, but we had announced that there would be around 285 system components, and we had completed only half of that number.

It was at this time that they asked me to revive our fortunes in the 35mm compact camera market. Previously I had been the one to lead the charge carrying the banner, but I was also anxious to train my successors, and so I formed a team of 10 development engineers. I gave them a year to develop any 35mm compact camera that they wanted. While they were doing that I worked on the OM. Then one day they told me that they had finished and wanted me to look at their work. They had written about 100 ideas on a blackboard. I didn't want them to make 100 cameras, so I told them to reduce the number. A few months later they had whittled the list down to 10. "It's still too many," I told them. "There should be no more three."

At the end of the year they said they were ready for me to look at their idea. I had made a point of not involving myself in their day-to-day efforts, and they had developed solidarity as a team. Autofocus technology had only just been introduced, and the Juspin Konica had only recently gone on sale. They told me that they had bought one, tried it, and found that it was very good. They were eager to make a camera like that.

That was against my philosophy. The camera was already on sale and we would have simply become involved in a price war. I told them that if they liked that camera I'd buy them one each. That would only cost about 200,000 yen, compared with the hundreds of millions of yen needed for developing a new model.

That was not a satisfactory end to a year's work. I told them to go back to the 100 ideas that they had originally produced. They had crossed out ideas to reduce the number, and their decisions had been guided by accepted wisdom. When they collected some of the better ideas from the rejected ones, a different response emerged. However, the results were still not quite in tune with my thinking, and so I was forced to make a choice and carry the banner once again.

With a camera you can carry with you everywhere, you'll never miss that once-in-a-lifetime moment again.

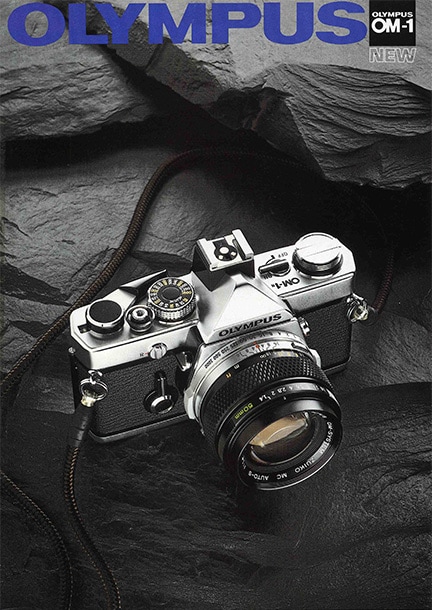

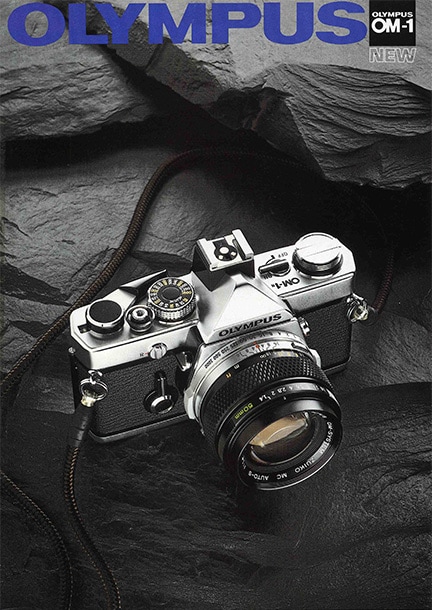

OM-1 catalog

The OM was conceived as an SLR that could be used to photograph anything from outer space to bacteria, but there are situations in which you can't use an OM. For example, you can't go to a wedding as the guest of honor and carry an OM over the shoulder of your tuxedo.

If you don't have a camera, you can't take photographs. I had realized that even if a camera could shoot everything from outer space to bacteria, users couldn't take any pictures if they didn't have the camera with them. In fact this was something that had been bothering me for many years.

When I was doing my factory training, I spent two years at our plant in Suwa. Suwa is a spa town, and there was a public spa next to my lodgings. In winter the place was so cold that towels would freeze solid, with the temperature reaching minus 23 degrees Celsius. Even with my window and sliding doors closed, the temperature in my room would also drop to minus 23, and a vase that my mother had sent me from Shikoku shattered when the water in it froze. Because it was so cold, the public spa was a popular playground for children. They would call in on their way home from school, and the water always became very dirty. So instead of taking a bath after work, I used to go in the morning before work.

On one such morning the driver of a long-distance truck decided to take a bath while passing through the spa town. He parked his truck in front of the public spa and went in just as I was finishing my bath. As I left I could hear a strange crackling noise. Sparks from the engine had started a fire, and because it was a gasoline-fueled vehicle the flames spread quickly. The driver came running out stark naked, but it was already too late. There was no water, so we couldn't fight the fire. It was a once-in-a-lifetime moment, but of course nobody takes their camera to the bath, so unfortunately I missed the opportunity.

Even if your camera can capture shots of outer space or bacteria, it's useless if you don't have it with you. I was determined to make a camera that people could carry with them everywhere. Nowadays we can take pictures with our mobile phones. I wanted to create something like that, but there were still no digital cameras in those days. For years I thought about designing a camera that you could carry with you always. I thought about it for a decade while I was working on the Pen and OM.

A caseless, capless camera would be small enough to fit in a breast pocket.

While the OM was small, it was an SLR, and there was a limit to how far we could reduce the size. We needed to create an even smaller camera. As I mentioned earlier, however, we faced resistance from Kodak when we developed the half-size Pen. The use of 35mm film was an absolute requirement in those days, and I was determined to create a smaller camera within that constraint.

If you take a 35mm screen and add a cassette to hold the film on both sides, you can reduce the width to a minimum of 105 millimeters. However, you can't reduce the height to less than 60-65 millimeters because of the finder. When it comes to thickness, the lens is the problem. There were folding cameras with collapsible lens, and I thought that this might be the answer, but I didn't want to move the lens much because there were so many interactions with the shutter and the mechanisms. So I decided to use a short lens that would be fixed in place. I began by setting the dimensions for my small camera, which I thought should be about 100-105 millimeters wide, 60-65 millimeters high and 30 millimeters thick, though I was prepared to allow a little leeway in these dimensions.

Once I had reached that stage, the task of making such a camera became a major challenge. A camera was a treasured possession, and people kept them in cases. It was expensive to make cases. We first used a soft case for the Pen. It was extremely popular, and Sony asked if it could use the Olympus soft case for its portable radios. However, something designed to be carried everywhere had to fit in a pocket, the smallest of which is the breast pocket of a shirt. My idea was to make a camera small enough to fit in that pocket. I wanted to make it as small as today's mobile telephones. And that idea led me to get rid of the case. It would be a caseless camera.

If I may skip forward a little, despite my youth I was invited to be the guest of honor at the wedding ceremony of the son of a camera case manufacturer, whose business was located in Tokyo's Koto Ward. The wedding was held two days after we had announced the caseless camera. There were about 650 guests, including many members of the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly. When it was my turn to speak, I told them that we had launched a caseless camera two days before, and I explained with great regret that we would no longer be using cases.

Another problem was the lens cap. The cap protects the lens from scratching and fingerprints, but it's a troublesome component. People lose them. The new camera had to be caseless, capless and small enough to fit in a shirt breast pocket. These were the conditions for my concept of a camera that could be carried everywhere. Our determination to meet these conditions led to the XA. It certainly didn't need a case, and in that sense it was an extremely unusual camera.